While the 1940s saw a terrible war and allied troops fighting on various continents, those Americans who stayed behind were assured of their role in the war effort not by fighting but consuming for the final victory.

While the 1940s saw a terrible war and allied troops fighting on various continents, those Americans who stayed behind were assured of their role in the war effort not by fighting but consuming for the final victory.

Even though many goods such as tires, gasoline, metals, fibers and sometimes even electricity were rationed, the marketing departments of countless companies still did their job and offered a huge variety of goods for the American consumer.

The war in Europe and the Pacific already had the state alarmed for a possible joining of forces with the allies. The long depression in the US was beginning to fade; jobs were available, there was a strong belief in a good future. Prosperity resurfaced and what else would a workforce now equipped with money to spend do but buy mass produced American merchandise?

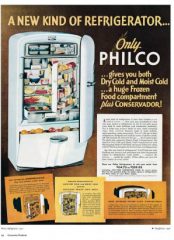

And after the attack on Peal Harbor (1941) the American economy was running at maximum speed to produce not only military goods but many new technical products, from refrigerators to cars and entertainment devices. The war effort also was supported by Hollywood, since now a huge number of war movies, espionage thrillers and semi-documentaries about life in the Armed Forces had hit the cinemas. (The consequences of the war, such as trauma, depression and mental disorders would only later become the subject of quite a number of Hollywood movies).

This level of industrial production was needed for peace times, as it turned out later. For then the nation entered a stage of prosperity unheard of, leading to high demand, mass employment and the baby-boom in the almost twenty years to come.

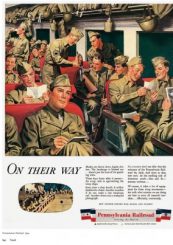

While a connection with military actions could be easily established with some products ready for sale in the ’40s, it is amazing to witness how the war effort found its way into commercials for cereals, cruise ships, steel, minerals, salt, cigarettes and a multitude of other consumer goods. This was one way to stimulate demands. And since brand names were not as popular as today, often repetitive and persuading text was employed and companies had various ads produced to feature one single product.

While a connection with military actions could be easily established with some products ready for sale in the ’40s, it is amazing to witness how the war effort found its way into commercials for cereals, cruise ships, steel, minerals, salt, cigarettes and a multitude of other consumer goods. This was one way to stimulate demands. And since brand names were not as popular as today, often repetitive and persuading text was employed and companies had various ads produced to feature one single product.

One sad fact here is the obvious invisibility of black servicemen in the ads; while there are plenty of pictures of black waiters, porters and housemaids instead. We need to keep in mind that the US of the 1940s was a segregated country.

Furthermore, war bonds were advertised very successfully, fueling American patriotism. In fact, it was only with the assistance of the bonds that the United States entered the war in the first place.

While sometimes marketing specialists are completely wrong when offering whole lines of products, we, nevertheless, can envisage what products were badly needed, what were luxury goods and how the general expectations in terms of design, keywords and usability must have been (or so we guess).

On 700 pages we can observe hundreds of beautiful commercial ads roughly divided into the sections food, alcohol, entertainment, the war, consumer products, industry, interiors and travel. This edition contains even more ads and text than the 2001 original print.

The introduction and short chapter headings come in English, German, Spanish and French. The reproductions come in excellent quality on heavy paper. We owe these to Jim Heimann, editor at Taschen, who opens the doors to his huge and internationally renowned private collection of pop cultural landmarks. He is also the author of a number of books on Hollywood, L.A. architecture and popular culture. (Heimann will also be the editor of the forthcoming volume of “All-American Ads. The 60s,” scheduled for 2015.)

Co-editor of “All-American Ads of the 40” is W. R. Wilkerson III, a journalist from California who wrote the introduction.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert (c) 2014

Jim Heimann, W. R. Wilkerson. III. All-American Ads of the 40s. Taschen, 2014, 704 p., ISBN 978-3-8365-5131-1