Some writers of fiction seemingly are blessed with a fathomless imaginative power, which is the basis for many science fiction and adventure stories. In the case of Tarzan (of the Apes), it is also owed to the very adventurous and at times fast-paced biography of the author of the Tarzan tales, Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875 – 1950).

Before he turned writer, he was a cowboy, joined the US Cavalry and worked in various functions for a mining company; always trying to satisfy the high expectations of his father, a former army major. Heart problems finally forced Edgar to leave the Cavalry after less than a year so that for the forthcoming time he was always dependent on his brothers to set him up in a number of businesses.

Before he turned writer, he was a cowboy, joined the US Cavalry and worked in various functions for a mining company; always trying to satisfy the high expectations of his father, a former army major. Heart problems finally forced Edgar to leave the Cavalry after less than a year so that for the forthcoming time he was always dependent on his brothers to set him up in a number of businesses.

His career as a full-time writer came about rather by accident when he was selling ads for dime magazines. In 1911 he decided that he could write pulp stories of questionable style as well as the next man. His first tale of Tarzan saw the light of day in 1912 in the All-Story magazine. The initial Tarzan novel (Tarzan of the Apes) was published in 1914.

What most readers of the Tarzan books did not know then, is that Burroughs’ very first published stories would not take place in the jungles of Africa but on the planet Mars. For Burroughs is also the inventor of John Carter of Mars and three sequels, as well as several other well-received science-fiction short stories and novels; at a time when this genre was all-fresh and had barely any tradition.

Nevertheless, Tarzan too, in his many adventures, confines his workings not just to the jungle; as it turns out, he helps British troops against the German army (Tarzan the Untamed, 1919), and moreover, works for British Intelligence as a secret agent, is a colonel in the British Air Force in WWII, then again, fights communist agents. While he roams the jungle, American cities or lost kingdoms, he poses also as adventurer, explorer and detective, which makes him a pre-Bond action star.

The long-lasting success of Tarzan is probably the effect of nagging fans and thousands of letters to both Burroughs and his publishers; readers demanded more and more stories. Had it been up to Burroughs, the saga had ended after a few novels and a compilation of short stories.

And Burroughs became quite a wealthy business manager, as he had plans besides his writings and went into real estate, bought property and founded the town of Tarzana (San Fernando Valley, today a part of the city of Los Angeles). He could do so, with income generated from publishing rights of his character in print, movies and TV.

Wisely, in 1923 he founded Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. to control any Tarzan-content that was sold, and thereby also cut down on taxes. He was one of the first authors to realize the importance of copyright and marketing for his own property. (For example, in 1975 the revenues from royalties of all Tarzan connected products earned Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc. around US$ 50 million.)

Tarzan’s effect on worldwide popular culture was intense and led to countless fan clubs; furthermore, he was used as a role-model for various movements and political parties. For example, the Tarzan reception in Israel was most unusual, where ten different writers wrote new Israel-centered stories about the hero from 1954-1964 alone (without legal permission from Burroughs).

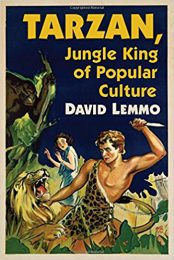

Lemmo in Tarzan, Jungle King of Popular Culture goes into much detail as he describes the many Tarzan movies, comic books, novels, short stories, marketing ideas, unlicensed copies, fan clubs, Tarzan revivals and actually anything there is to know about the immortal jungle superhero.

And why in a time of quickly advancing technology a character – or rather, an archetype – who is clearly on the “natural” side of life and prefers the company of animals to that of men (still) is so well-liked in many kinds of media.

Any fan of Tarzan, early science-fiction or students of popular culture (marketing) will enjoy this title, to say the least.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2017

David Lemmo. Tarzan, Jungle King of Popular Culture. McFarland, 2017, 236 p.