Film studies introduced countless movie fans to genres and varieties of films that were once praised just by small groups of fans. It was usually decades after the initial film releases, that, for example, the fascination with film noir, certain types of the westerns, or screwball comedy went beyond the tiny groups of connoisseurs and film students.

Apart from academic studies, additional information comes from individual researchers, film buffs or photographers who enlarge on such topics; as does Hollywood historian Mark Vieira from Los Angeles, who has already provided useful information and photographic footage of several films noir.

Apart from academic studies, additional information comes from individual researchers, film buffs or photographers who enlarge on such topics; as does Hollywood historian Mark Vieira from Los Angeles, who has already provided useful information and photographic footage of several films noir.

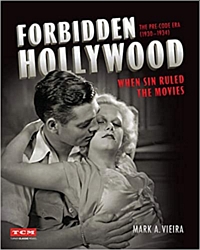

His last book Forbidden Hollywood is on a number of American movies from the early 1930s that – retrospectively – became known as “Pre Code Era” productions. They were subject to investigation, large protests, and were either severely edited to be permitted public screening or banned from cinemas altogether.

For reasons that today would not have anybody raise an eyebrow, but in the 1930s the sometimes explicit presentation of partial nudity, allusions to sexual (and extramarital) activities, spicy dialogue, scenarios that aimed at the seduction of women, and general “immoral conduct” let the “moral authorities” triumph over both the film industry and the demand of the vast majority of cinema goers. Finally, in 1934, a strict production code was imposed on all national movie productions, and censorship also hit imported foreign films.

Already some years earlier, in 1930, the first so-called (Production) “Code” was issued, on behalf of the actions of clergymen, club women and people who deemed themselves the moral guardians of American culture, like the “Legion of Decency.” But the movie companies easily found ways to bypass or ignore the code, that let the companies more or less voluntarily control all dialogue and scripts for scenes of violence, romantic relationships of any sort across the color line, illegal drugs, homosexuality, miscegenation, sexual perversion, nudity, perfect and easy to copy criminal plots, white slavery, provocative dancing and lustful kissing, among other things.

Already some years earlier, in 1930, the first so-called (Production) “Code” was issued, on behalf of the actions of clergymen, club women and people who deemed themselves the moral guardians of American culture, like the “Legion of Decency.” But the movie companies easily found ways to bypass or ignore the code, that let the companies more or less voluntarily control all dialogue and scripts for scenes of violence, romantic relationships of any sort across the color line, illegal drugs, homosexuality, miscegenation, sexual perversion, nudity, perfect and easy to copy criminal plots, white slavery, provocative dancing and lustful kissing, among other things.

However, even when all US studios signed the code agreement, it would not have any effect on the films, as with the advent of the Great Depression audiences were given an overdose of exactly the prohibited features to foster box office sales.

This raised even more protest from the conservative guardians and in 1934 one Joseph I. Breen issued national censorship, supported by the Production Code Administration. This time, the industry in a way surrendered. This was a huge censorship milestone, for a very young, but powerful (sixth-largest) American industry.

As Vieira points out, it was a struggle for power, money (and survival on the studios’s side), and it had to do with religious beliefs. “The market was mostly Protestant: The industry was mostly Jewish-run. Yet a Midwest Catholic minority gained control. …. Hollywood’s attitude toward sex was counter to Catholic doctrine of the day, which taught that sex was for married people and should not be discussed or shown, at least of all in a place as public as a movie theater. Theaters came to be viewed as incipient brothels, corrupting everyone who entered them.”

The movies in question which caused that turmoil, today are labeled “Pre-Code” or “pre Breen”; and contrary to popular belief, not all were produced by some small studios on a tiny budget. Some came from the larger companies with star actors and star directors.

The movies in question which caused that turmoil, today are labeled “Pre-Code” or “pre Breen”; and contrary to popular belief, not all were produced by some small studios on a tiny budget. Some came from the larger companies with star actors and star directors.

Forbidden Hollywood spotlights twenty-two of those films that led to the installment of the new Code of 1934. Among the collection are classics such as Little Caesar, Dracula, Frankenstein, Possessed, Red-Headed Woman, Tarzan and his Mate, The Public Enemy, and She Done Him Wrong.

The films were attacked by the press, then were cut (severely edited), shorted and “mutilated” to be shown at all, and still, in some states or territories, they were banned.

Steps taken were drastically carried out, as all movies (new or reissued) would have to stand the test at the Joseph Breen Office, occasionally several times.

Vieira not only presents hundreds of high-quality film stills and publicity shots, he also goes into detail concerning the making of the movies. However, what really makes the book unusual is the amount of “confidential” data from telegrams, diary entries and general film business correspondence. In this way, he takes the reader back to the sets, the shooting, editing, rearranging and lets the reader eavesdrop “… on conferences between producers and writers, read nervous telegrams from executives to censors, and listen to conversations between censors and directors, where artistic decisions meant shifts in power – and money – when one-third of a nation was desperate.”

The book is organized in chronological chapters that refer to each year from 1930 to 1934, starting with a long introduction to the style of filmmaking in the Roaring Twenties. His sources for the many details are interviews, biographies and articles from newspapers and trade papers.

The book is organized in chronological chapters that refer to each year from 1930 to 1934, starting with a long introduction to the style of filmmaking in the Roaring Twenties. His sources for the many details are interviews, biographies and articles from newspapers and trade papers.

A highly informative book, as it not only gives insight into the genesis of the Production Code years, but also a lot of information on studio politics, artistic decisions, the reaction of actors and editors to censorship and the self-awareness of movie company executives of the time. Both entertaining and a lesson in movie production politics under changing circumstances.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2019

Mark A. Vieira. Forbidden Hollywood: The Pre-Code Era (1930-1934): When Sin Ruled the Movies. Running Press (Turner Classic Movies), 2019, 256 p.