The period of American sound film until roughly the mid-1940s was dominated by soundtracks and extradiegetic audio based on mostly sweet string orchestras, allusions to classical compositions and ballads. Then, in the 1950s and 60s, soundtrack composers increasingly used popular music of the decade before for police/detective/spy action productions, which would be in large part jazz, the country’s main musical attraction and dance floor magnet of only a few years earlier.

“It’s often assumed that early TV ‘crime jazz’ – a reasonably accurate designation for the music that accompanied early dramas starring cops, sleuths and virtuous investigators from various professions – sprang from the big screen’s post-WW II fascination with the scandalous characters and seamy behavior found in Hollywood’s artfully moody film noir B pictures.”

“It’s often assumed that early TV ‘crime jazz’ – a reasonably accurate designation for the music that accompanied early dramas starring cops, sleuths and virtuous investigators from various professions – sprang from the big screen’s post-WW II fascination with the scandalous characters and seamy behavior found in Hollywood’s artfully moody film noir B pictures.”

In the early 1950s, with the introduction of TV broadcasts, production companies and film studios took great care in hiring not only the best composers available, but also big bands and large classical orchestras with exceptionally good performers to record hundreds of series theme songs and film scores. The scores in focus here had one thing in common: they all use techniques and rhythms mostly associated with jazz, often integrated in a pattern of pop tunes and string arrangements. And the work for movie productions was a welcome paycheck for professional jazz musicians.

To use Derrick Bang’s words “…. serious buffs have long cherished the roughly three decades – from the early 1950s, more or less, to the early 1980s, less or more – that encountered a wealth of great stuff from veteran and up-and-coming jazz cats eager to “shade” the adventures of cops, private eyes, crusading journalists, impassioned lawyers, spies and secret agents. Hundreds of albums and chart-placing singles emerged during those 30-ish years, and a great deal of that music is overlooked these days … along with the trends that fostered it.”

These great soundtracks, some of them masterpieces in their own way, are not to be confused with what in the early years of this century was tagged “lounge music” and appeared on countless easy listening CDs from the vaults of the big record labels. The style Bang devoted this volume to, is much more complicated (as is the nature of jazz arrangements) and at the same time very easily consumable and memorable. And it took first class composers to successfully combine these two aspects, as hardly a moviegoer would stand experimental music or free jazz as a soundtrack for 80 minutes at the cinema.

Extraordinary artists such as Quincy Jones, Nelson Riddle, Henry Mancini, John Barry, Elmer Bernstein, David Shire, Laurie Johnson, Pete Carpenter, Edwin Astley, Kenyon Hopkins, Lalo Schifrin, Jerry Goldsmith, Earle Hagen, Neal Hefti, John Williams, and many others who expertly used jazz licks, riffs, rhythms, and its instrumentation are reintroduced here, even though some have already received academy awards for their works.

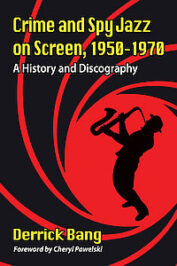

Although some may argue that there actually is no exact definition of “Crime and Spy Jazz,” a comprehensive discography or a study of jazz-inspired soundtracks was not available until now. “Inspired by the shady corners, characters and cliffhangers that graced the TV shows and movies of the mid-20th century, this is the first book and discography that compiles and traces this music’s history. For all the intense attention and cataloging of music inspired by the years spanning the 1940s to early ’80s, crime/action jazz just wasn’t among the genres covered,” says Cheryl Pawelski in the book’s foreword.

As it would be impossible to recreate the moods, instruments and sound effects of each movie or TV series mentioned, Bang summarizes the styles and working techniques of many famous composers/musicians to introduce their crime and spy jazz works chronologically. (The emphasis here is mostly on domestic productions, due to space; only a few European films and shows are mentioned).

He briefly sums up plot and orchestration of a few hundred movies, including theme, introduction, extra-diegetic effects, plot and musical additions as sounds from diegetic (audio heard by the movie characters and audiences alike) juke boxes, turntables, melodies sung, whistled or other sonic effects. Certain films with exceptional audio deserve mention on several pages.

Crime and Spy Jazz on Screen is organized in fourteen chapters, starting in 1947 and moving on chronologically to 1970. It is impossible to tell which section stands out, as they all are excellent in their own way, dealing either with a thematic subject or several composers who did groundbreaking work and delivered magnificent soundtracks in a particular year.

For example, chapter 10 deals with the year 1966, the main topics are the TV series Batman, Jericho, Blue Light, T.H.E. Cat, Mission: Impossible, The Green Hornet, Hawk, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., The Felony Squad, the movies Blindfold, How to Steal a Million, Arabesque, Gambit, Assault on a Queen, After the Fox and many other works that use a certain style of crime and spy jazz score. (In this chapter, for instance, also two great Italian composers and their work, Pietro Umiliani and Piero Piccioni, are mentioned). Accordingly, many statements by Lalo Schifrin, Nelson Riddle, Stu Phillips and other composers inform the chapter, also commenting on who took on when what musician/composer left and how that film score influenced others to come, be it by rhythm, instruments, tempo or vocalist used or what soundtrack album or 7-inch record came out that way and was covered by how many artists later.

Readers will familiarize with the most successful TV and movie productions, orchestras, featured musicians and recording locations, producers and (sometimes their recycled ideas involved), and the personal recollections of many artists involved in recording a peculiar score. Movies, shows or individual show episodes are dissected into musical key scenes, themes, cues, underscores, leitmotifs, ostinatos and their variations in relation to plot and action.

The book comes with a 26 page discography and lots of information on recording companies, deals with film companies, film set details, musicians featured in countless performances, last-minute alterations (as assigning the theme’s melody to an electric guitar instead of a trumpet), and tons of other aspects.

A valuable (and rather wittily written) find for all fans of spy movies, jazz buffs or soundtrack collectors with an interest in the golden years of American TV and movie production. Both volumes have their companion website: screenactionjazz.com.

This text covers volume one. The book’s companion volume Crime and Spy Jazz on Screen Since 1971: A History and Discography will be reviewed here soon, so please check back.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2020

Derrick Bang. Crime and Spy Jazz on Screen 1950-1970: A History and Discography. McFarland, 2020, 284 p.