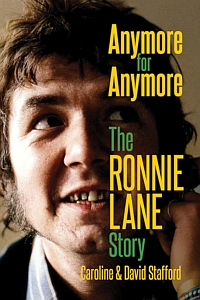

Authors Catherine and David Stafford’s new title on one of Britain’s most important bass players, Ronnie Lane (1946-1997), successfully fills some information gaps rock music lovers may have encountered, concerning show biz and London’s music scene of the 1960s and 70s.

Their Anymore for Anymore: The Ronnie Lane Story tells of his humble beginnings as a guitar player with several amateur bands and pub entertainer who in 1965 was a founding member of legendary Mod band The Small Faces.

Their Anymore for Anymore: The Ronnie Lane Story tells of his humble beginnings as a guitar player with several amateur bands and pub entertainer who in 1965 was a founding member of legendary Mod band The Small Faces.

And that was just the beginning of a loud, wild and in part unbelievable musical career of Ronald Frederick Lane from Plaistow, London (nicknamed “Plonk” for the way he played bass), unfortunately with more downs than ups.

It is a record that covers lots and lots of touring, partying, LSD consumption, massive drinking, hotel room destruction, blackouts, tragic romance, and very bad and exploitative management. First, while on Decca Records, the band was badly ripped off by their manager Don Arden. He at no time forwarded them their royalties, and to keep them calm paid each member 20 pounds per week, took care of unlimited shopping bills on Carnaby Street (as all band members were sharp dressers and preferred flashy Mod gear) and provided them with drugs and a house. That way, the band never saw the millions they earned from the label.

Like many other young musicians, they were unsuspecting, inexperienced and naive. When the band moved to Immediate Records in 1967 and trusted one Andrew Loog Oldham, something very similar happened. For many years to come, there were fights and lawsuits as the band was never paid in full.

Theirs is one major tale of the English music biz of 1960‘s London. In the end, among other things, Ronnie Lane could look back on a string of 17 consecutive Top 40 singles altogether, that he either wrote or co-wrote. The list includes Small Faces classics such as “Itchycoo Park, ” “Tin Soldier,” “All or Nothing,” “Lazy Sunday” or the Faces’ “Ooh La La” and “Flying.” The Small Faces were probably the band most cheated out of their royalties and music sales of the decade.

Today, Lane unfortunately is largely forgotten, and except for fans of early rock music, his name would probably not be recognized by most pop music lovers, which is a pity, since he was a great song writer and outstanding bass player. And considering the musical output of Ronnie Lane, especially in collaboration with Steve Marriott, there is no question that he deserves the same attention as other prominent song writers of the time. Like Lennon/McCartney or Jagger/Richards. Although not the world’s greatest singer, Lane can be heard on The Small Faces’ “Something I Want to Tell You,” a rarity of sorts. (Years later, he would sing on the Faces number “Stone.”)

The years with the Immediate label probably were the most creative ones of Lane’s career, as The Small Faces would release ‘their own Sgt. Pepper,’ namely the brilliant concept album Ogden’s Nut Gone Flake in 1968. Then, in early 1969, Steve Marriott left the band. Lane, Ian McLagan and Kenney Jones were not just taken by surprise but also jobless. The gang soon ran into Ronnie Wood (former member of The Birds and future Rolling Stone) and one Rod Stewart. Both were available, as The Jeff Beck Group had recently folded. Inevitably began the second calling of Ronnie Lane (and the remaining Small Faces except Marriott, who started out with Humble Pie), as a member of the Faces, where they all got together.

Here, too, heavy partying, drinking, drug use and the like naturally happened, as a sort of motor that kept the entire enterprise going. As a live band, they were excellent and going to a Faces concert must have felt like attending a vast party, according to most reviews of the time. With the Faces, Lane finally toured the US many times where they had a huge following. (In later years he would eventually move to Austin, Texas and get married to an American.)

In 1973, Ronnie left the band, turned part-time farmer, moved to Wales, and started new musical projects. He received real money for his work with the Faces, however, he was not happy. Among his new projects was the “folk” band Slim Chance. (Their 1975 release “Anymore For Anymore” obviously was the inspiration for the title of the book at hand).

Ronnie also brought back a 26ft Airstream Caravan from an American tour and had it converted into a recording stage with all the latest equipment. It was called the LMS, “Lane’s Mobile Studio.” (Some tracks of The Who’s Quadrophenia and Clapton’s Rainbow Concert were recorded there.)

The years after Slim Chance were rather disastrous, in terms of musical success, several plans to reunite former bands did not take off, Lane became some sort of a loner and at times encountered severe creative burnout. Those topics are at the center of roughly the last third of the book.

The 320 pages are well divided into something like Lane’s years with the Small Faces, The Faces, his “circus days,” and finally several, mostly unsuccessful projects that failed to earn him much money in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

In general, the last two chapters present Lane’s personality a bit more detailed; he could be a complicated person, was a fan of Indian spiritual master Meher Baba and open to philosophical aspects of life. Nevertheless, he also would always be torn between those aspects and working-class straightforwardness.

He died in Trinidad, Colorado, essentially penniless, old pals from his successful days, like Ron Wood, Jimmy Page, Rod Stewart and a few others had to support him. Lane was diagnosed with MS in 1977, his condition got progressively worse every year and for the last part of the 1990s, he basically was unable to walk or care for himself. In 1997, he caught pneumonia that finally ended the life of a great musician.

However, the title’s emphasis is mostly on his music, which in his days also meant the many “extras” it came with and how to survive them: drugs, alcohol, blackouts, severe mental and health problems that followed. The sum of it destroyed many of his contemporaries.

The Staffords paint a very colorful picture of Lane’s life and times, backed by extensive research and additional information provided by his family, friends and hundreds of fellow musicians. The book reads as comfortable as a long article in a music mag, as the authors use a quite entertaining style, that at times is sarcastic and even downright comical.

Be assured that every two pages or so for most events reported they will throw in bits and pieces from the pop universe that either happened simultaneously or shortly after. Or it did happen a few weeks ago, causing this or that event that finally would bring together producer/engineer/drummer or whoever to record that demo, decide on this band name or would go separate ways after a fight only to form that or another band.

So after Ian McLagan’s autobiography, Kenney’s account of his musical life and a recent excellent biography on Steve Marriott, here is the solid counterpart, the missing link if you want. All four Small Faces (and some Faces) get their stories told. That, for the moment, will have you dive deep into the days of two very important bands from the British 1960s and 1970s.

Recommended reading, quite funny and melancholy at the same time.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2023

Caroline and David Stafford. Anymore for Anymore: The Ronnie Lane Story. Omnibus Press, 2023, 320 p.