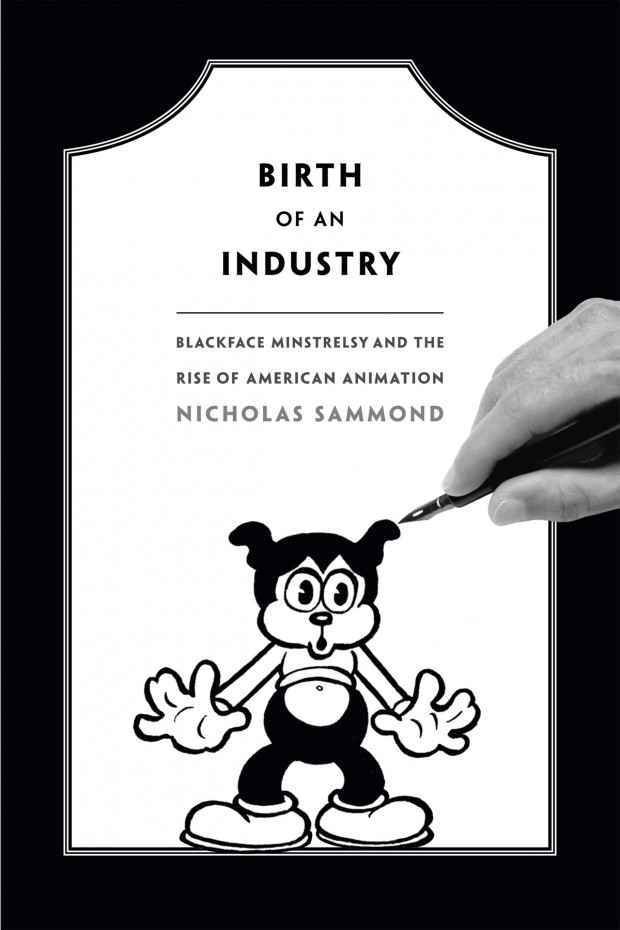

The mere mention of the word ”minstrelsy“ brings back numerous unpleasant, racist, stereotypical and humiliating issues of the past. It is interesting to find out then, that many of the most popular cartoon characters were actually modeled on or even continued the line of minstrelsy characters: the most popular would be Walt Disney’s (early) Mickey Mouse, others are the charters Bugs Bunny, Felix the Cat, Betty Boop’s Ko-Ko and similar ones.

Sammond with particular focus on the American animation industry comments on “the relationship between imagined blackness and imagined whiteness at the beginning of the twentieth century … [The study] may cast some light on why, in the face of overwhelming evidence that blackface is alive and well today, it is almost always treated as if it were a relic of a historically remote past that Americans have moved beyond – even as we demonstrate with pathetic regularity that we actually haven’t. Mickey mouse isn’t like a minstrel; he is a minstrel [emphasis in original].“

Sammond with particular focus on the American animation industry comments on “the relationship between imagined blackness and imagined whiteness at the beginning of the twentieth century … [The study] may cast some light on why, in the face of overwhelming evidence that blackface is alive and well today, it is almost always treated as if it were a relic of a historically remote past that Americans have moved beyond – even as we demonstrate with pathetic regularity that we actually haven’t. Mickey mouse isn’t like a minstrel; he is a minstrel [emphasis in original].“

At the heart of this study lie the sociocultural ties that connect blackface minstrelsy, vaudeville shows, early animation technology, a changing American entertainment industry in the early 1910s and various forms of bold and hidden racism, basically borrowed from late 19th century fantastic stereotypes about people of African American decent.

It is interesting to learn that at certain times old patterns of vaudeville received a renaissance, thereby still citing and manipulating hatred and images of white supremacy. “Cartoons (or vaudeville, or live film) were of a form of entertainment that supplanted a dying blackface minstrelsy; rather, they were a permutation of minstrelsy, a part of a complex of entertainments at the dawn of American mass culture of which live minstrelsy was a fading element, and film, including animation, a rising one.”

The book offers a mass of information and dates on the topic of early animation film and minstrelsy. At times, this unusual load of data may even overburden the reader. However, several arguments get repeated over and over and may leave the reader confused, particularly when it comes to identifying racism, stereotypes and bias.

This may be due to the complex topic itself and the dangers of being not PC in discussing minstrelsy’s origins and uses, but in relation to the art of animated film this could finally result in a complete refusal of presenting or even liking cartoons for political reasons, no matter if they were produced in the 1920s or the 1990s.

Fact is, that many basic characteristics of cartoon characters can be traced back to issues of minstrelsy, racist caricature, popular fantasies about African savagery and helpless (thus comic) forms of protest.

But then, it is this problematic chain of arguments that is the central theme of the book and it may just need periodical mention.

In the book’s rather long conclusion chapter (40 pages), it is made very clear that blackface minstrelsy and vaudeville techniques and routines from the 19th century are not merely the ancestors of American cartoon and animation film art, but that they have survived and constantly resurface in modern day cartoons. Identifying these has become much easier after reading Birth of an Industry.

Nicholas Sammond is Associate Professor of Cinema Studies at the University of Toronto. He has published on animation and Walt Disney before.

Since Birth of an Industry is about a very visual sort of media, there, fortunately, is a digital companion (http://scalar.usc.edu/works/birthofanindustry) that offers all kinds of sketches, films and pictures. This feature is a most useful addition that should be available for many more titles.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2016

Nicholas Sammond. Birth of an Industry: Blackface Minstrelsy and the Rise of American Animation. Duke University Press, 2015, 400 p.