To uncover the motivation behind the purchase of millions of basically purpose-free small “crap” objects, Wendy Woloson describes in great detail the giant industry behind the “novelties” and “labor saving inventions” that actually are little more than useless cutlery, buttons, dolls and other commodities. Objects that were originally produced only to convince buyers that they spent their money on useful things and minute artifacts.

“The number of gadgets – from combination corn grinders to miracle fire extinguishers – began increasing in the 1840s and exponentially so after the Civil War, supplementing reliable and familiar tools. Gadgets embodied the seemingly limitless creativity of American ingenuity and drive toward greater efficiency. ‘New-fangled’ devices offered faster, easier, more enjoyable processes for doing everything from washing clothes to peeling apples. Gadgets came to seem like personal servants, promising to turn the burdens of work into entertaining leisure activities.”

“The number of gadgets – from combination corn grinders to miracle fire extinguishers – began increasing in the 1840s and exponentially so after the Civil War, supplementing reliable and familiar tools. Gadgets embodied the seemingly limitless creativity of American ingenuity and drive toward greater efficiency. ‘New-fangled’ devices offered faster, easier, more enjoyable processes for doing everything from washing clothes to peeling apples. Gadgets came to seem like personal servants, promising to turn the burdens of work into entertaining leisure activities.”

Woloson writes about these generally cheaply produced objects – that include plastic vomit, Joy Buzzers and Whoopie Cushions – in a very amusing style. In six chapters she tries to find reasons why in a country that once was populated by people who produced useful tools and appliances manually and in good quality, citizens suddenly and easily became almost addicted to foreign produced, cheap merchandise.

This tendency was supported by a new advertisement idea that suggested personal relations between companies and consumers, and that led to even more articles of the same kind. “More alluring still is the crap that isn’t just cheap but free. Since the first decades of the nineteenth century, long before Cracker Jack tokens and cereal box prizes, merchandisers were rewarding loyal customers with giveaways and prizes. … All of it was crap, but it was free crap, which was all that mattered.”

And yet another main line of crap distribution – basically just a new sales strategy – started in the late 19th century with the invention of the souvenir spoon and assorted cheap objects, seemingly incredibly rare and collectible goods. “…[T]he market really took off in the mid-1950s, when ceramics manufacturers began aggressively marketing commemorative plates. … The manufacturers of these myriad objects democratized collecting, which had been a fairly exclusive activity. … Intentional collectibles, however, enabled ordinary people to enjoy the thrill of the hunt, the satisfaction of acquisition and curation, the pride of display, the company and camaraderie of like-minded people, and (nominally) the economic benefits of investing.”

Wendy Woloson, associate professor of history at Rutgers University-Camden, lists countless crap articles and their respective backgrounds, manufacturers, collectors and marketing strategies, and examines almost three centuries of crap sales on American soil. If you thought, you knew in which disguises and shapes crap was sold, often to make very little profit margins, be prepared for some surprises. The many stories, pictures and advertising ideas she reveals about peddlers, sales performances (changing over the decades), cheap chain stores and novelty goods with obviously no purpose are fascinating. It is accompanied by dozens of historical ads, flyers, store pictures and promotional materials.

This very amusing title considers certain features of the American consumer, or rather, tries to reveal the reason why there has been so much crap around and why the crap available at present is even worse (as it is made from cheap materials impossible to recycle and after it was trashed now probably pollutes giant areas of ocean floor).

How this all could happen for decades – out in the open – is at the center of the study, as “… this book is both a history of crap and a history of consumer psychology. Why did Americans welcome crappy goods in their lives in the first place, and why have we encouraged them to stay…[?] … There is nothing more American than crap.”

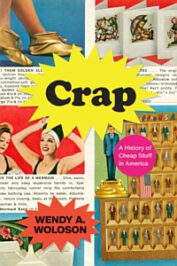

Her journey to the origins and variations of “crappiness,” quite philosophical at times, is well worth reading, as she elaborates on the strong drive in consumers and collectors alike to possess and amass crap. Here, even the cover design of the study (with metallic typeset and novelty publisher icon) is inspired by her findings.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2021

Wendy A. Woloson. Crap: A History of Cheap Stuff in America. University of Chicago Press, 2020, 388 p.