Kicking off roughly in the early 1950s, British and American science fiction authors of the new breed, labeled New Wave later, brought massive changes to the genre and changed the way the future of mankind was perceived. They spoke for a growing readership that was hungry for new visions and speculative prospects, now being prepared for even more fantastic settings.

The New Wave would in a way render the writers of science fiction’s “Golden Age” obsolete; nevertheless, the classical authors politically were rather right-wings. Those science fiction forefathers grew up in different times, had distinctive agendas and mostly a positive outlook and more often than not envisioned a prospering future planet Earth that came with space exploration and modern technologies.

The New Wave would in a way render the writers of science fiction’s “Golden Age” obsolete; nevertheless, the classical authors politically were rather right-wings. Those science fiction forefathers grew up in different times, had distinctive agendas and mostly a positive outlook and more often than not envisioned a prospering future planet Earth that came with space exploration and modern technologies.

The new generation, generally left-wingers and still under the impression of the Cold War, nevertheless, perceived the many small and huge changes in American and England’s societies. Such changes, liberating effects and fresh visions of a forthcoming world led to very different visions of the future in science fiction novels. “The New Wave still had its astronauts and interstellar explorers, not now they could be found psychologically crumbling under the physical and mental pressure of space flight and the directives of the oppressive military bureaucratic apparatus behind them.”

Furthermore, one of the key figures in editing science fiction stories, Michael Moorcock, entered the scene in 1964, and was largely responsible for introducing unknown talent in New Worlds magazine.

He also edited the extremely successful anthology Dangerous Visions in 1967. In the early 1960s, science fiction by the newcomer authors became even more revolutionary. As it now additionally voiced extremist ideas of the Left, allied with the Underground Press, and presented societies and worlds between radical ideas, political extremes, psychedelic nightmares and life under permanent supervision by the state. “Nevertheless, almost all [writers covered in this title] were focused on shaking things up and testing the limits of morality and critical tolerance within and beyond the genre.”

Now the protagonists in the stories and novels were critical, cynical and basically questioned the entirety of orders, greater plans, or directives that would render societies numb, passive or keep them in an artificial state of happiness. Furthermore, the postwar years saw the rise of the paperback, that could exist and prosper through the unstoppable hunger of audiences for original stories, be they in print or on TV. Magazines that carried the stories before were not that important anymore, as audiences in the 1960s and 1970s demanded novels. And cheap paperback production could meet those needs.

The 21 authors of the sections cover the beginning and the wild years of the New Wave from roughly 1950 to 1985, either giving a good overview of a subject and then again, musing on one author or a single novel exclusively. Unfortunately, apart from the rather short introduction, each chapter basically starts and ends with regard to its own and unique topic. Maybe a bit more of editing, with regard to a more linear order (as in Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, 1950 to 1980, by the same editors) would have made an even better book. Some of the sections, they come with an average length between four and eight pages, seem a bit out of place as they occasionally seem to be inserted more or less randomly into the book’s outline.

Apart from that, and depending on your personal interests, the title consists of most readable texts, with the usual shifts in quality, considered that 19 authors will deliver in 19 different styles.

It is very likely that even longtime fans of the genre will encounter a couple of new authors on the pages ahead, so diverse and specialized are the respective chapters on authors, publishers, sub genres, single novels or protagonists. The titles introduced, discussed in length or brevity thematically range from adventure stories, tales heavily informed by political, radical, racial or feminist themes to crude pulp action, erotic fiction, detective stories and any kind of astronaut/explorer topic and fantastic and grotesque blend thereof possible.

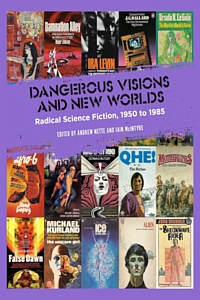

Back then, marketing demanded that potential readers should be alarmed by such subjects as soon as they saw the book cover. “The promise of science fiction, in its ability to transcend and travel beyond the limits of the present, was not met not only by authors but also illustrators and designers. The influence of psychedelia, surrealism, and experimentation in general of book cover art during the period can arguably be seen most strongly in the science fiction field.”

Some of the highlights presented here unquestionably are the texts “The Energy Exhibition: Radical Science Fiction in the 1960s” by Nicolas Tredell, a solid Mick Farren portrait by Mike Stax, and Rebecca Baumann’s piece on Essex House, a Los Angeles publisher of adult erotica/science fiction literature famous for highly artistic and psychedelic book covers.

As usual, the Australian editorial team of Andrew Nette, a writer of fiction and nonfiction, and Iain McIntyre, musician, author, and community radio broadcaster, deliver first-class background as well as detail on a rather neglected, but highly interesting and thrilling side action in the history of popular culture. And again they present their 8 x 10” volume in perfect layout and have it illustrated with hundreds of beautiful and rare paperback covers that, alone, are reason enough to put the title on your shelf. Dangerous Visions and New Worlds is a fantastic title in every aspect and in the literal sense.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2022

Andrew Nette and Iain McIntyre (eds.) Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950–1985. PM Press, 2021, 224 p.