For several decades, a very distinctive form of African American minstrel show was the most popular form of entertainment for black audiences in the South, its fame covering almost the entire country by and by. The beginning of this art form (that was in parts of the country available until the late 1940s) and its effect on what we today know as either blues, jazz, soul or hip hop lie in this development, and it is fascinating to backtrack this artistic spirit, as done by Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff.

Both authors collaborated already back in 2009 when they presented Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895. While Abbott works at Tulane University (at the Hogan Jazz Archive to be more exact,) Doug Seroff is an independent scholar and music researcher from Tennessee.

Both authors collaborated already back in 2009 when they presented Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895. While Abbott works at Tulane University (at the Hogan Jazz Archive to be more exact,) Doug Seroff is an independent scholar and music researcher from Tennessee.

While conducting their research over many years, the team found plenty of evidence for one of their key conclusions: that the commercial so-called “coon” songs (a racist term for originally early forms of black folklore and blues performed by either white singers in blackface or as the term was used more frequently, for the performances of artists of African American decent) „.. spilled into turn-of-the-century black vernacular culture, where they seem to have served a transitional function. Two-way traffic between the grass roots and the black professional stage, intensified by the popularity of ragtime coon songs, cleared the way for the ‘original blues.’“

Nevertheless, the very expression “coon” in connection with variations of those early forms of ragtime, blues, but also comedy lines as well as dancing routines and a music show category, was once a trademark of sorts, drawing audiences to tent shows, theaters and circus side shows since then there was no way of recording the performances. For the majority of the white sheet music buyers and tent show visitors the coon songs and ragtime were the same thing anyway.

Once the industry of minstrelsy and tent show entertainment was successfully taken over by black performers, this new generation of artists laid the foundations for modern popular music, starting out with ragtime, blues and early forms of jazz. In that process jobs for hundreds of musicians, dancers, writers, arrangers, conductors and sidemen were created. Jobs that prior to that development simply did not exist.

Still it was hard work for those who endured, since “black performers faced exploitative business practices and biased journalistic criticism in the northern entertainment world, and violent racial antagonism and Jim Crow prohibitions in the South.”

The ability to improvise, find variations, patterns and individual style within those limits – as manifested in the very nature of blues and jazz – may have come from tight boundaries such as these.

While carefully investigating almost every single edition of the Indianapolis Freeman and the powerful Chicago Defender, papers predominantly read by black audiences and additionally referring to mainstream trade papers such as Variety and Billboard, an enormous amount of information was gathered.

Referring to all kinds of information such a new trends, extraordinary talent future tours, commercial success and innovative capacity of the many traveling shows of musical comedy, tented minstrels and circus annex troupes’s certain styles, expectations and features become obvious. So naturally many reviews and announcements refer to the superstars of the genre such as George Walker, Bert Williams and most prominently Ernest Hogan, author of the 1896 smash hit „All Coons look alike to me.“

For what in the 1940s may have been the Harlem Apollo theater and what today may be represented by some music television award, back in the early days of the 19th century was the collapsible stage of the traveling tent shows and minstrel comedy; it was there where the entertainment stars gave their performances.

The data collected here is almost overwhelming and is well worth looking at, let alone all the data on the many female blues artists of the 1920s and 1930s; more than a few of them actually started their musical careers in vaudeville, like Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith and Daisy Martin.

(This review covers the 2012 paperback edition; the book originally was published in 2007).

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2013

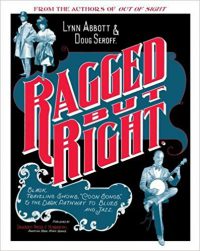

Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff. Ragged But Right: Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. (American Made Music). University of Mississippi Press, 2012, 200 b&w Illustrations, 472 p.