The latest work edited by Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette has the focus on pulp fiction published in English and connected to and influenced by the Counterculture and ideas of revolution. The emphasis is on “the long sixties,” meaning the aftermath of that truly revolutionary decade that was at work long into the 1970s, in part still until the early 1980s.

In similar works by the same authors, such as Girl Gangs, Biker Boys, and Real Cool Cats: Pulp Fiction and Youth Culture, youth culture and its exploitation in pulp books is documented excellently.

In Revolution and Counterculture, the basic topics are, of course, the air of revolution, spread mostly by members (and consumers) the so-called counterculture who were both admired and hated, depending on who you may have asked in the 1960s and 1970s.

In Revolution and Counterculture, the basic topics are, of course, the air of revolution, spread mostly by members (and consumers) the so-called counterculture who were both admired and hated, depending on who you may have asked in the 1960s and 1970s.

Black protagonists and settings connected to the Civil Rights Movement, Sit-Ins, wildcat strikes, and a new view on community and housing models were other important features of both the times, and the fiction related to it.

And the energy, violence and completely different outlook on life as it clashed with the ideas of “the establishment.” (NB: “To stick it to the man” means to voice protest, fight established mindsets and powers, to attack, if necessary with violence, the government to cause a revolution that would alter societies wherever possible).

Those ideas were put at the center of the many, many pulps that flooded the market for decades. “The thousands of novels produced from the 1950s to 1980 that deal with social change remain fascinating for a number of reasons. On a historical, cultural and sociological level they give the modern reader an insight into how political and social transformations and challenges were portrayed and understood by authors, publishers, and readers. Many, probably the majority, of the authors responsible for these novels had little if any connection to the movements or communities depicted in their fiction.”

Most cheap paperbacks were quickly written by second-rate authors or hack writers. Those were, mostly, not exactly brilliant novels, and they were published equally quickly to satisfy a seemingly unstoppable hunger for easily accessible stories and sensation – this time dealing with “strange” developments in society.

“In many cases, their portrayals were negative and inaccurate, filled with observations and material befitting the sensational nature of the publishers they worked for.” Needless to say that the “average Joe” on the street, possibly ignorant of the latest political developments, would take on a very negative opinion when concerned with newspaper headlines or news on left-wing activities, Black Power, juvenile delinquency, hippies, motorcycle gangs or just new forms of urban living. Although very often, these pulps would be the sole source of a somewhat – although fictional and prejudiced – deeper understanding of alternative ways of life.

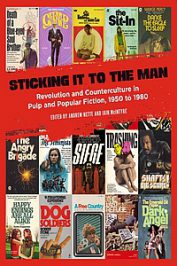

However, the usual fate of such a novel was to be purchased maybe at a gas station, drugstore or train station, to be consumed on the way to work or in a few hours at home, only to end up in the garbage can later. (Many of these original pulps today are sought after collector’s items, due to their status as first editions and because of their unique cover design).

Notably here in the overview of that group are some solid texts, for example on the great and still underestimated African-American crime fiction writer Chester Himes (by Scott Adlerberg). Moreover, an overview of Robert Beck’s (aka Iceberg Slim) fiction by Kinohi Nishikawa, pulp feminism (by Bill Osgerby), and the Shaft universe in literature and film (by Steven Aldous).

Some topics of these pulps receive more attention in McIntyre’s and Nette’s study, as these would sell more copy back then; the pulps were necessarily aimed at mass audiences and would usually not use complicated vocabulary or plots. These are texts on lesbian pulp novels, gay pulp, strictly local themes such as regional countercultural stories from Canada, Australia (featuring Aboriginal Australians) or England, books specifically aimed at male straight audiences, the pulp campus novel or fiction that dealt with the Vietnam war experience.

Some of the pulp authors are featured in interviews such as Nathan Heard (Howard Street) and M.F. Beal (Amazon One). “This collection brings a number of overlooked, entertaining, and revealing texts and writers from 1950 to 1980 back into the light. It also explores how popular culture in the form of fiction dealt with and portrayed the radicalism and social shifts of the era.”

The list of contributors includes furthermore Gary Phillips, Woody Haut, David James Foster, Emory Holmes II, Michael Bronski, David Whish-Wilson, Susie Thomas, Jenny Pausacker, Linda S. Watts, Maitland McDonagh, Brian Coffey, Molly Grattan, Brian Greene, Eric Beaumont, Bill Mohr, J. Kingston Pierce, and others. Some essays are extended, around 15 pages, while other texts are as short as just three pages.

Again, a wonderful title that is most welcome as it elaborates on specific aspects of pulp novels of a certain period with great essays and tons of fantastic book cover reproductions.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2019

Iain McIntyre and Andrew Nette (eds.) Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980. PM Press, 2019, 336 p.