In 1935, when teenage brothers Earl and Bill Bolick from Catawba County (NC) first performed publicly, they were inspired by the many duets and family band outfits of early country music.

Back then, sibling/brothers/sisters duets or entire band families were popular, like the Carter Family, the Delmore Brothers, the Carlisle Brothers, the Monroe Brothers, Mac and Bob, the Shelton Brothers, or the DeZurik Sisters. Many of those competitors also added old hymns and sentimental songs to their repertoire.

Back then, sibling/brothers/sisters duets or entire band families were popular, like the Carter Family, the Delmore Brothers, the Carlisle Brothers, the Monroe Brothers, Mac and Bob, the Shelton Brothers, or the DeZurik Sisters. Many of those competitors also added old hymns and sentimental songs to their repertoire.

The duo’s first shellacs only one year later, on which they accompanied their singing with guitar (Earl) and mandolin (Bill), were successful, and they went on to perform as a sibling duet on local radio stations. Their blend of old-time music, country music and bluegrass sung with their perfectly pitched soft voices made them famous for a while.

But they could not look back on an uninterrupted string of hits over the years, as some of the super stars of country music of that time could. To give their sound some variation, they briefly hired other artists, usually banjo, guitar and fiddle payers (such as Richard Hicks and Curly Parker). Looking back, their irregular success was probably the fault of their record label RCA, that failed to promote them accordingly, although they had some hit records in the late 1930s. “On the Sunny Side of Life” and “Turn Your Radio On” became classics.

Both brothers joined the armed forces in WWII and continued recording after their discharge, but retired as a duo in 1951. In 1962, they got together again, only to disband in 1965, largely because RCA did not reissue their material while the folk revival was in full swing in the US. Then in 1974 they reunited for some last shows at Duke University, the Bluegrass Festivals in Gettysburg and Virginia, followed by a final studio album for Rounder Records in 1975.

Bill Bolick († 2008), massively disappointed by record labels, ignorant audiences and modern sound, towards the end of his career often depicted their lives as professional musicians as difficult, if not failures. His idea of performing music was strongly connected with authenticity and the way their songs were performed. Just as they were originally played in the 1930s, without sound effects, heavily altered studio recordings or electric instruments. Seemingly his brother Earl († 1998) was less bitter about his musical career. After their breakup he started a successful vocation at Lockheed aircraft.

The stories of many famous country and bluegrass bands are well documented these days, thanks to the efforts of eager fans and journalists. In this case, however, author Dick Spottswood could rely on and include Bill Bolick’s notes and written accounts, and even include several interviews he had given over the decades. So this title probably holds all the information that there is on the duo.

Spottswood provides some extra-large appendices: roughly two-thirds of the volume are reserved for the Blue Sky Boys’ discography and a very elaborate annotated song list, which is highly unusual and will be welcomed by musicologists and fans of old-time music. Thanks to Bill’s notes, this book on Country music stars is not on the Blue Sky Boys exclusively, but also retells the story of country music of the 1930s and 1940s. With lots of insights on touring, marketing, radio stations, relocating, traveling, song selection and performances.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2019

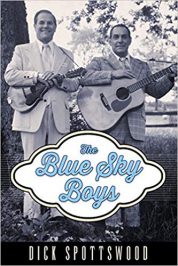

Dick Spottswood. The Blue Sky Boys (American Made Music Series). University Press of Mississippi, 2018, 354 p.