There are very few masters of the harmonica (or “harp” as the instrument is called colloquially by musicians) that had a lasting impression on rock music, as English and American groups in the 1960s during the Beat era covered many blues originals that featured a harp.

Among the most prominent players, we find Little Walter and one Billy Boy Arnold, whose autobiography now is a feast for blues fans and music historians.

The harp players strongly informed the blues with the instrument’s ability to “bend” notes, like a guitar player can, who will make a note shift between two tones.

Shortly after the introduction of the mass-produced amplifier, the harp also was played amplified, which gave the instrument even more power and similarity to the human voice, as would the loud, halfway distorted sound coming from a speaker.

Blues harp players would enrich their style with that method as early as 1948.

William Arnold, better known as Billy Boy Arnold, a Chicago native (*1935) is one of the major blues harp players who influenced generations of musicians. Stylistically, first a disciple of blues legend Sonny Boy Williamson (1914 – 1948), he decided to become a professional musician when still a kid. Always paying tribute to his great idol who got killed just a few weeks after their second encounter when Arnold was only 13. “If it wasn’t for Sonny Boy’s records, I would have never tried to play the harmonica. Once I heard him, I wasn’t goin’ to stop … It was Sonny Boy’s records that made me seek out the blues world, and when I met him, that was my first contact with it.”

Little wonder his memoir is dedicated to this influential musician. Arnold met very many of Chicago’s blues elite already in his youth, often by just talking to them after a show, in a restaurant or while out on the streets of Chicago. And sooner or later, he would find himself recording or sitting in with them, and over time, he developed his own harp sound, became a renowned singer (and bass player) and professional musician.

His story is witness to the massive changes in music reception and blues performance, that finally would become electrified all over. Arnold in his early youth still experienced acoustic blues, while he became one of the pioneers and specialists of the eclectic harp generation, so his insights and memoir are first class information.

His career really took off when he played harp on Bo Diddley’s “I’m A Man” and “Bo Diddley” in 1955. Arnold became a huge success with two of his own recordings, “I Wish You Would” and “I Ain’t Got You” the same year. Both songs were covered by The Yardbirds and others later (while he never received substantial royalties for it). He became a household name in the Chicago area and did lots of tours, but by the end of the 1960s recorded less and less. He is a regular artist at blues festivals and has never stopped recording entirely; his last studio recordings are from 2019.

Arnold saw and heard a lot, and he was around enough to be an eyewitness to two periods of blues history. Combine that with lots of stories about Tampa Red, Memphis Slim, Junior Wells, Elmore James, Walter Davis, Jazz Gillum, Blind John Davis, Willie Dixon, Otis Rush, James Wheeler, Jimmy Reed, Good Rockin’ Charles, Bo Diddley, Little Walter, Mighty Joe Young, Magic Sam, Harmonica Slim, Johnny Young, Eddie Ware, Muddy Waters, actually any blues man of some standing, and you get a taste of what the book at hand is like.

Each of the nine chapters is breathtaking and diverting, and each one is a treasure for blues historians and fans alike. Probably chapters seven and eight stand out, as they give you the next big development – white players on stage in Chicago’s blues clubs in the early ‘60s – in Arnold’s words in a nutshell.

“What some people don’t understand is that the blues was an all-black thing in the 1940s and ‘50s. …The other races didn’t even know it existed. There was no white people involved.” That changed, mostly with the success of guitarist’s Paul Butterfield’s Blues Band. “Butterfield and Charles [Musselwhite] was the first two white guys who was really doin’ the blues and was really accepted by the black audience and everybody. … It was Paul who got the black blues bands their first gigs on the [Chicago] North Side, ‘cause he knew the club owners. And the white audiences didn’t know about Muddy or Wolf or Buddy Guy either, until they started playin’ at Big John’s. … Over time, more white people was listenin’ to blues than blacks, who were sort of weanin’ themselves away from traditional blues.”

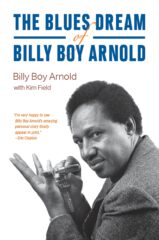

Arnold’s memory at 86 (!) is still excellent and this is his story, written down with the assistance of Kim Field, author and musician. And there is more: first-hand information about massive exploitation of black artists by labels and distribution lines, stories about blues club polices, touring schedules, the tight network of blues and jazz artists in the cities, copyright infringements, royalties that never came and the creative genius behind tons of blues classics. The title comes with an extra discography, three miniature maps of Arnold’s Chicago neighborhood, and 57 halftone pictures.

The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold is a highly recommended jewel, both as a document of blues history, a documentary of African-American life in the aftermath of the Great Migration, the story of electric Chicago Blues, and lots of deep insight on the South Side music scene, told by one of the last insiders around.

Review by Dr. A. Ebert © 2022

Billy Boy Arnold and Kim Field. The Blues Dream of Billy Boy Arnold. (Chicago Visions and Revisions Series). University of Chicago Press, 2021, 288 p.